Speaking With Robin Richardson

Robin Richardson is the author of two collections of poetry, including Sit How You Want forthcoming with Véhicule Press. She is also Editor-in-Chief at Minola Review. In this post, assistant blog editor, Madeleine Wattenberg, speaks with her about unsympathetic poetry, the value of ugliness, and the relationship between written and visual art.

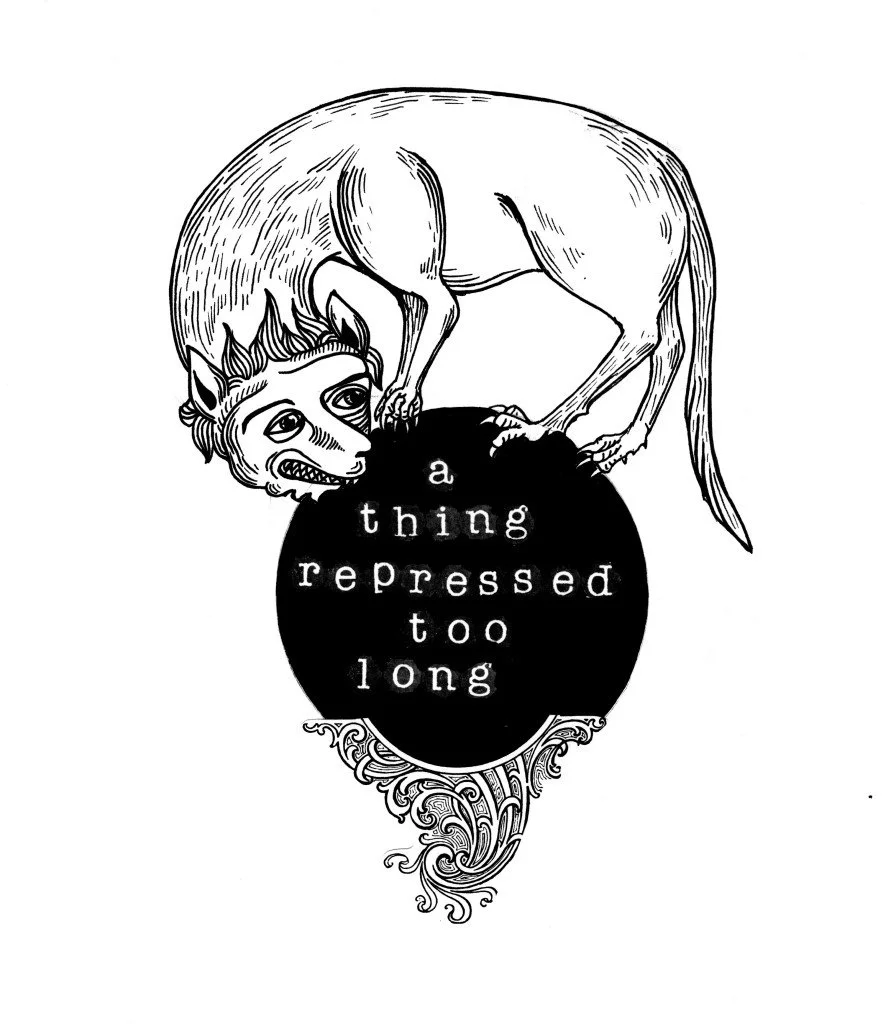

Robin Richardson, “a thing repressed too long,” Ink & Collage, 6 x 8 inches

Madeleine Wattenberg: I really enjoyed the essay you published in North American Review about the differences between the sympathetic and unsympathetic voice. In the essay, you state that, “The unsympathetic poet enters into the frightening territory of writing the truth of who she is and sees, regardless of the acceptable or admirable norms she’ll find approval in.” I wonder if you could connect this to your experience specifically as a woman who writes following (or against) a tradition of the male “universal” voice in poetry. Were there poets you found as particular models of this voice that helped you in discovering it yourself?

Robin Richardson: Thank you. I think it’s brilliant you put universal in quotation marks. That’s exactly how I see it: a patriarchal construct, an attempt at claiming that one’s work is objective and concerned with universals, as though all reality weren’t filtered hopelesslessly through our few flawed senses.

To me subjectivity and uncertainty are as close to true as I will ever come as a poet.

While according to many still established in traditional patriarchal ways of thinking, that paradigm of universal certainty, scientific provability, and so forth, is the only true way. So yeah, there’s tension between me and this establishment, however, society at large seems more hospitable to this and many other shifts now, particularly compared to the way things were when I first started out in writing. There are two contributors to this sense I have, I think, of increased hospitality. The one is a shift in North American society at large, particularly when it comes to taking women more seriously in our own terms. The other contributor is more personal. The older I get and more sober I become the more confidence I have in my own conviction, and thus the more respectably I am received as I bring that conviction into fruition.

She’s not a poet, but one of my greatest guiding lights in this transition has been Leslie Jamison, whose essay The Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain gave me permission to be honest about what traditional men might find repulsively cliché. I also want to throw back to Sylvia Plath here, whom the scowls of men put me off of for years until finally, thinking for myself, I realized there was genius in her hyperbolic self expression. A few other influences here are Marina Abramovic, Natalie Eilbert, Louise Glück, Fanny Howe, Anne Boyer, Melissa Broder, Mary Ruelfle. I would have once upon a time said Frederick Seidel, whom I worshipped, but I’m less and less able to deal with robust men. Everything comes and goes in phases as I grow.

MW: In the essay, you also briefly mention that the unsympathetic poem, not the sympathetic poem, promotes empathy. Can you expound on this connection?

RR: The sympathetic poem is crafted in service of the author. It makes one look intelligent or innovative, or, in the case of this “universal” notion you put forth, which I can’t get out of my head now, it makes one seem a masculine sort of authority. I think of all these poems written by white men about the strife of the third world and so on. It comes secondhand and from a sense of the author’s own importance and “seriousness.” It puts nothing on the line, offers up no vulnerability, and does nothing to actually portray the truth of its subject matter, because only the subject, speaking for herself, could provide the “truth” of her experience. It’s somewhat colonial to me, and difficult to digest.

In contrast to this, the unsympathetic writer puts herself on the line, risking vulnerability and exposure of the unflattering angles the sympathetic writer dodges with skill and preoccupation with externals. So, in a world where only the flattering photos are posted, and the easy to digest stories shared, it is a crucial service to one’s fellow to expose the ugly, the sad, the unflattering. It’s in this sharing that we begin to feel less alone.

This is where isolation ends, and empathy, solidarity even, begins. I could go on for pages about the illuminating and healing power of sharing true stories but I’ll stop here with the urge to start listening and asking questions; to start sharing the things that make you feel most unlovable.

MW: You also run a series of Unsympathetic Poetry Workshops. What is the pedagogy of the Unsympathetic Voice? Do you have specific tools or exercises to encourage participants to embrace their unsympathetic voices?

RR: It’s primarily organic. I like to begin by reading the above mentioned essay, or some other piece along the same lines, followed by a brief introduction, and a few ground rules about workshopping procedures. The cohesive element of the workshop is my personal guidance, which steers discussion in the direction of excavating the heart of each participant’s poem, focusing on what needs to be done in order to best serve that heart. Form, sound, metaphor, appearance, all fall in service of the heart. The trouble is so few poets, particularly beginners, are able to identify that heart on their own. That’s where the workshops become effective, and honestly, it’s also where they become terribly intimate and fun.

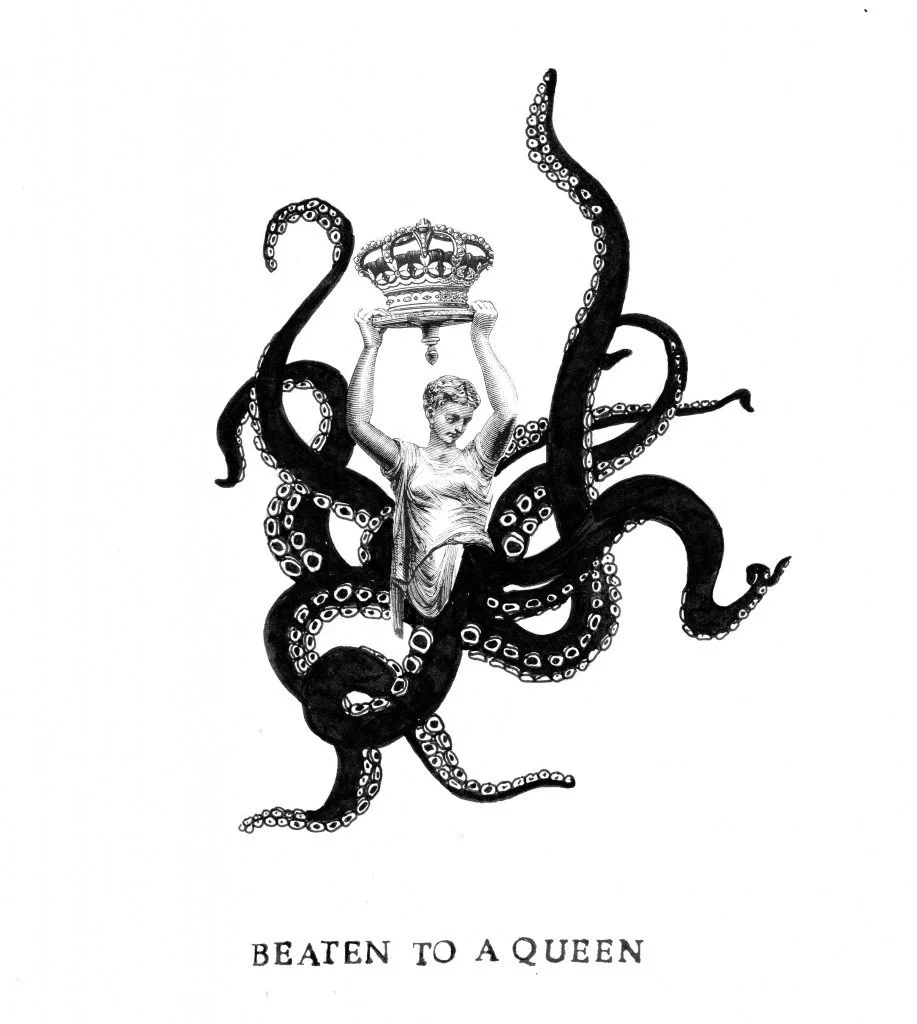

MW: I’m very interested in the relationship between your work as a poet and your work as a visual artist. Like your poetry, your art seems unsympathetic in its voice. Both art forms begin with a blank space. Can you talk about your process from that point—how poetry and visual art fill in the field similarly or differently? Do you draw inspiration from the same sources?

RR: Yes, both the written and visual do come from the same source. The source is unconscious.

I believe my unconscious is infinitely more intelligent than my conscious thinking self, and so I work hard not to let my intellect get in the way of my real intelligence, which is based in intuition, instinct, and archetypal, symbolic thinking.

In this way the blank page is never really an issue. I do not think about where a thing will end up or what it will mean until it’s almost completely manifest.

Robin Richardson, “Beaten to a Queen,” ink & collage, 6 x 8 inches

MW: Many of your prints also incorporate small lines of text. What’s the relationship between text and image? Does your visual art help you construct images from language or visa-versa?

RR: I enjoy bouncing the two off of one another. It’s really just another way for me to take control away from the intellect and give it to the intuition. In combining words and text I am forced to make compromises in meaning and in control. There is more room for unintentional connections here and I believe it’s in this intentionality that my unconscious wisdom best manifests.

MW: Do you see poems and prints as art-objects? Do you have different objectives for the two art forms? Different audiences?

RR: I suppose I do. I like the idea that my work can exist on the two levels: on the one easily accessible to the masses via publication, primarily online, and on the other, purchasable as an intimate, collectible, signed object. Both relationships are valuable in their own right, and it’s a privilege to be available on both levels.

Robin Richardson, “truth gets me wet,” ink & collage, 6 x 8 inches

MW: You founded the all women’s journal Minola Review less than a year ago, and since its founding the journal has grown to be a paying and soon-to-be in print market. First, it’s really exciting to see a space that promotes women’s voices thriving. So thank you! Second, how can our readers support this project?

RR: Thank you! Yes I love what Minola Review has become. Six of our strongest pieces will be appearing in print next year as a magazine within a magazine in CAROUSEL. After that we will be releasing an annual print anthology, which, by the grace of god, will be sustaining enough we can go on paying contributors, and releasing annual print anthologies indefinitely. Again this allows Minola Review authors to exist both on an easily accessible online platform as well as in an intimate book format.

By the time this interview comes out our kickstarter campaign will have ended, but if you believe in the cause, which is a safe and nurturing space for women’s writing, then I urge you to donate through our website’s easy donation porthole.

You can, of course, also buy yourself and all your friends a copy of the anthology when it is released.

MW: And last, what are you reading right now? What should we be reading!

RR: Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. It’s very polarizing so I can’t promise you’ll love it but I’ve read 400 pages in three days, and have wept half a dozen times. It will also make you want to reach out to your friends, or adversely, will make you terribly jealous if you don’t have many.

Robin Richardson is the author of two collections of poetry, and is Editor-in-Chief at Minola Review. Her work has appeared in SALON, POETRY, Tin House, Partisan, Joyland, The North American Review, and Hazlitt, among others. She holds an MFA in Writing from Sarah Lawrence College. She has been shortlisted for the CBC, Walrus, and Lemon Hound Poetry Prizes. Richardson’s latest collection, Sit How You Want, is forthcoming with Véhicule Press. Poems from the collection have been adapted to song by composer Andrew Staniland for The Brooklyn Art Song Society, and premiered in 2016 in New York. Richardson’s Memoir “Like Father” is represented by Samantha Haywood at Transatlantic Agency.